An introduction to social norms

In this section you will find information on key social norms theory.

What are social norms, and why are they important in SRHR?

A person’s decisions around contraception and reproductive health are influenced by a variety of factors: their knowledge of where to go, which methods to choose, the time they have to go there, the costs involved, their attitudes towards contraception,… Some of these can be addressed in the short term by improving access to services and reliable information. Yet the social norms that are persistent in their community are strong factors as well. Social norms also significantly influence sexual and reproductive health and rights by shaping gender inequality, power dynamics, and privilege. They affect individual choices, interpersonal communications, and joint decision-making processes. Social pressure impacts decisions regarding birth spacing, method choice, and family size. Additionally, social norms play a crucial role in the acceptance and support for access to contraception, especially for marginalized and vulnerable groups. Effectively addressing these norms presents a key opportunity to achieve long-term change in SRHR.

While social norms barriers can be hard to address, doing so is key to ensuring long-term change to establish an enabling environment for women and girls.

Social norms are the unwritten rules that people in a group or community follow to know what is considered acceptable behaviour. They help guide how people act and interact with each other.

Note that social norms are not always barriers – sometimes, you can leverage a positive social norm to help our work. You can learn all about these approaches in the section on designing social norms activities.

Key takeaways

- Social norms work is SBCC work – it’s important to start by understanding specific behaviour change goals

- Not all barriers we identify are social norms, but they are a key category to ensure long-term impact. Differentiating between the kinds of barriers we face is important for impactful programming

- Consider when a barrier might be linked to a norm – for example, why are people often worried about returning to fertility after using an FP method?

How Social Norms Change Works

This section provides a theoretical framework to keep in mind while we think about activities that address social norms.

How does social norm change actually happen?

There are 4 phases:

Phase 1: Change social expectations

A successful social norms intervention shifts both individual attitudes and social expectations. In this phase, the programme aims to leverage individual-level opportunities and take them up to the community level – remember the socio-ecological influence model. It is in this phase that some individuals will start acting according to our desired behaviour, either despite or because of how it was presented in relation to the relevant social norm.

Triggering change: before you can create a core group within the community that can drive further behaviour change, you need to trigger a need for change or to open conversations.

When designing activities to do this, here are some key considerations:

- Initiate dialogue, either with individuals or in groups – get people talking

- Dispel misconceptions or inaccurate beliefs relating to the harmful behaviour

- Avoid reinforcing and normalising the negative behaviour by insisting on its high prevalence

- Do not criticise people’s cultures or beliefs. Rather, demonstrate that the new behaviour is in line with community values, e.g., delaying childbirth is safer for mother and child

Broadening the scope: fundamentally, norms shift at group level. Involving a wider community is key. Some considerations:

- Think about your target audiences: go back to your reference group analysis and consider including different activities for multiple groups

- Identify influencers and agents of change from within the community to lead the programme

- Create safe spaces for critical reflection among community members: Enable reflection, deliberation and debate among key individuals and groups

- Seek change at the whole-community level, to ensure new behaviours are widely accepted

- Be aware of power imbalances relating to gender and age (for example, young people’s agency is often a lot more limited in speaking up about these topics)

FAQ: Can talking about a negative norm, risk reinforcing it?

Yes, it definitely could. The rule of thumb is: if most people are against it, let everyone know. If not, campaign to start changing individual attitudes, but don’t focus on how widespread the behaviour is – rather on promising alternatives. If the negative norm is based on perceptions, not reality, then showing that the majority do not actually adhere to the norm. A good example of this was PSI’s “Chill” project in Kenya, targeting 10-14 year-olds. There was a perception that kids their age were all having sex and that by not being sexually active, you were uncool. But in fact, very few kids were having sex at that age and by using likeable characters to reinforce it and language that made it “cool” to abstain (“ what’s the rush? I’m chilling”) they shifted the perception around this.

Phase 2: Publicise the change

Once you start seeing change, it is time to shout it from the roof tops.

Who should be spreading the word?

- Coordinate the shift among people ready to change, in a visible manner: amplify, give a platform to champions/role models and the benefits of new behaviours

- Develop a diffusion strategy to build knowledge of the change in similar and neighbouring communities

- Use trendsetters, first movers, influential small groups or popular media to amplify the buzz

- Don’t work with everyone and anyone, but the key stakeholders necessary to make a difference: the positive deviants and role models to put forward; the influencers which will help you be heard; the powerholders to reassure and partner with; the existing organised groups to start the local dynamic with; the leaders to steer the process; the young and marginalised community members to empower.

Phase 3: Build a supportive environment

To ensure the norm change is sustainable, we should take care that the messages we spread through our activities, can be embedded in the community fabric.

- Provide opportunities for the new behaviour to be carried out by people beyond the original reference network

- Help create new rewards and sanctions and ensure they are monitored and carried out by relevant members of the community

- Form guardian coalitions with influential actors that will advocate for the new norm in and outside of the community

Phase 4: Evaluate, improve and evolve

For more details on this, please refer to the dedicated Monitoring & Evaluation page.

- Evaluate programme success and scale-up opportunities – see measuring social norms page

- To change norms at scale, embed the programme into national systems, supported by social movements and coalitions of partners. But the initial tactic might be to create a proof of concept in pilot areas. Make your interventions scalable from the start, try them out, and if they work, sell them to the right people at the top.

Social Norms at MSI

This section provides an overview of our approach to social norms at MSI, where social norms feature in our gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) programming, how they underpin our approach to sustainable demand for public sector strengthening and their role in behaviour change.

It should be particularly useful for those of you who need to talk about our work externally!

How we approach Social Norms SBCC

- We work with communities, for communities, and this is deeply embedded in our ways of working

- We use data to inform decision-making and tracking impact

- We leverage, shift, and counter social norms as relevant

- We engage not just our primary target audience, but their influencers too

- We are led by our country programmes to ensure we leverage existing opportunities in the communities to further MSI’s mission

Our theoretical frameworks

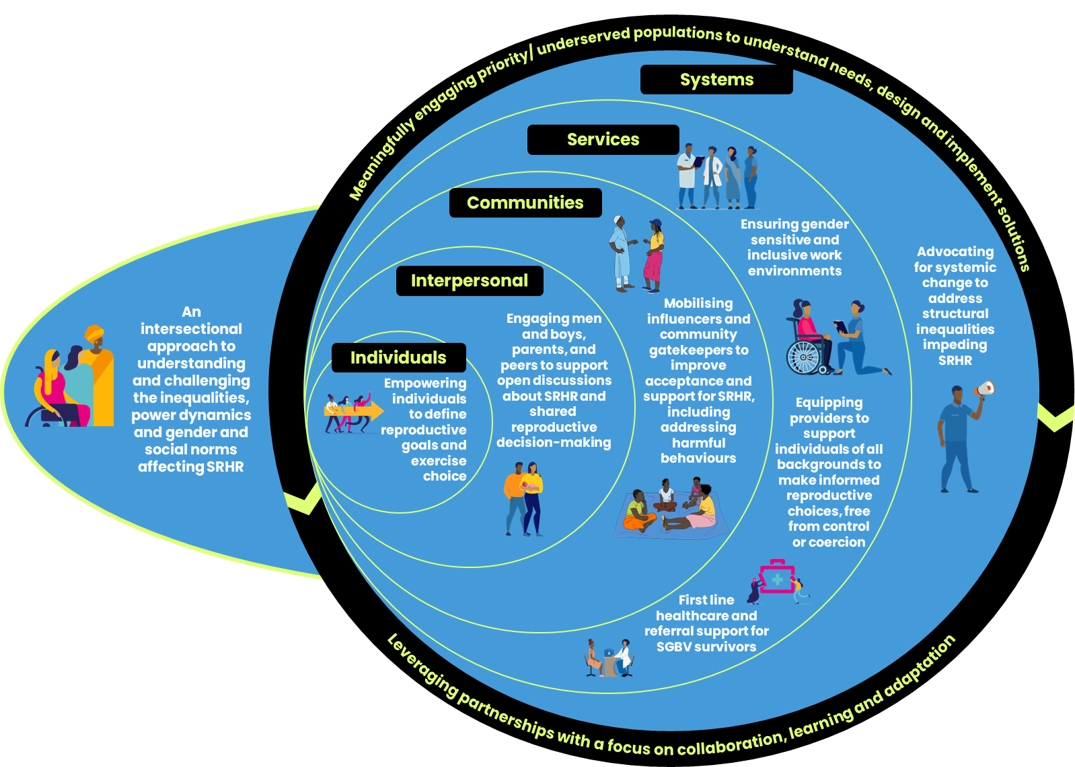

Understanding and programming to influence the social norms affecting SRHR is critical to MSI’s approach to addressing gender equality and social inclusion (GESI). MSI aspires to be GESI transformative in our programming, meaning where possible we try and address the root causes of the inequalities affecting who has power and privilege in the contexts where we work. Our GESI programming seeks to strengthen the agency of vulnerable and marginalised communities, including women and girls, and ensure they have the voice, choice, and power to exercise their rights to sexual and reproductive health. We cannot do this without addressing the social norms affecting reproductive choice and empowerment, this is reflected in our MSI GESI programming framework.

For more on GESI programming at MSI see here (internal link).

The potential to deliver long term change in the expansion of reproductive choice and empowerment means that addressing gender and social norms is a key component of our approach to sustainable demand in public sector health systems strengthening. Alongside working with in partnership with governments and a range of community engagement approaches, gender and social norms are an essential feature of the way we hope to build a long-term enabling environment. See here (internal link) for more on sustainable demand.

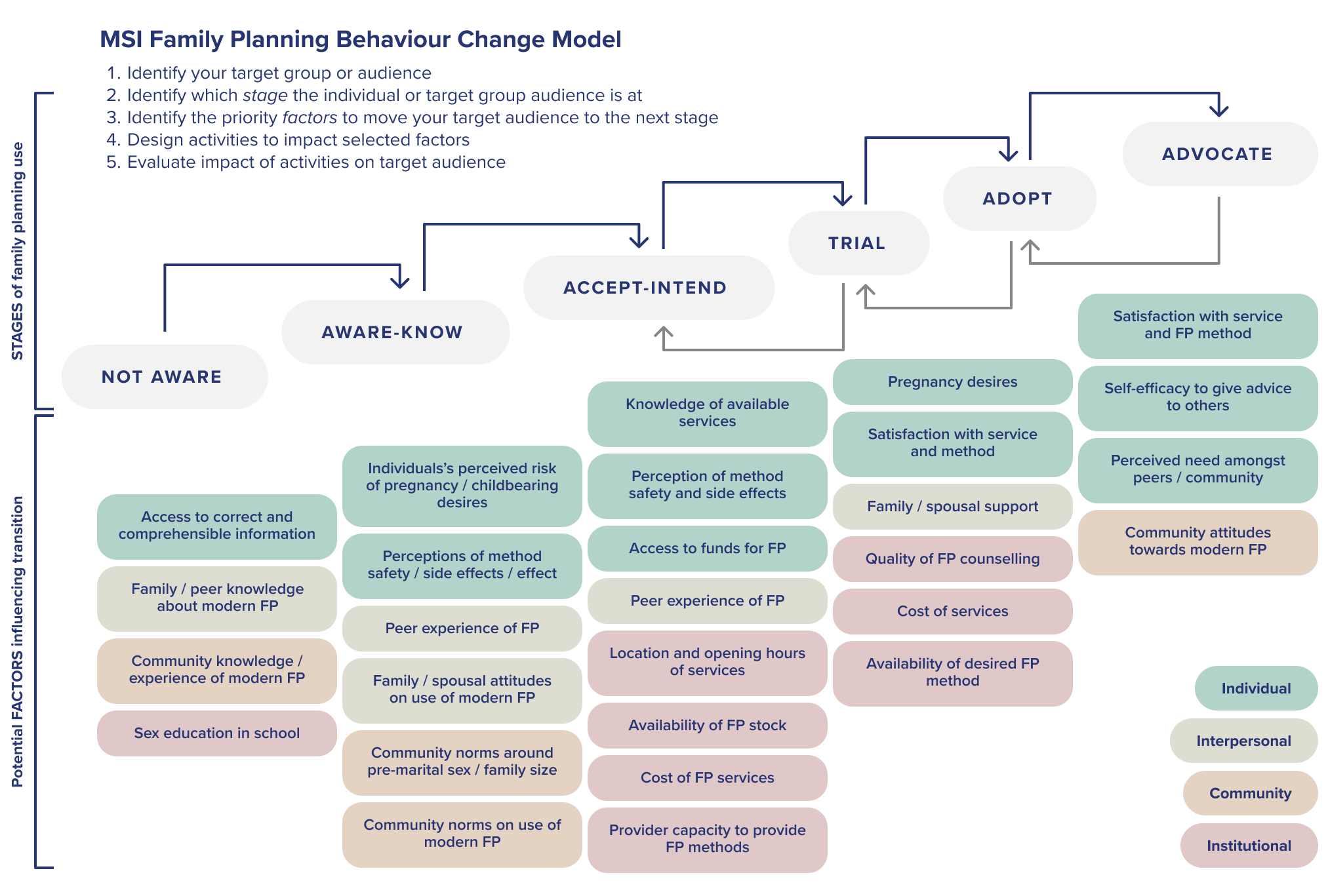

Finally, at MSI we look at communications through the lens of behaviours. This is why we developed our MSI behaviour change framework. A quick refresher below, full guidance is saved here (internal link). This framework helps remind us that different norms, exert different influences, depending on where an individual is on the behaviour change pathway.

Social Norms Jargon Buster

Social norms language can be confusing! Use this page to get a quick refresher on the key definitions.

Social norms

Social norms

The perceived informal, mostly unwritten, rules that define acceptable and appropriate actions within a given group or community.

Empirical expectations

Empirical expectations

“What I think others do” in relation to the social norm

Normative expectations

Normative expectations

“What others expect me to do”

Injunctive norms

Injunctive norms

A norm you are expected to follow and expects others to follow

Descriptive norms

Descriptive norms

What you think others are doing

Pluralistic ignorance

Pluralistic ignorance

A wrong perception of what others think/do; when people mistakenly believe that everyone else holds a different opinion than their own.

Sanctions

Sanctions

How others react if people do not conform to the norm – the consequences of going against the norm.

Reference group

Reference group

The people who shape/influence the norm

Exceptions

Exceptions

Under what situations it is acceptable to break the norm

Patriarchy

Patriarchy

The social system in which positions of dominance and privilege are primarily held by men. Men hold more decision-making power than women.

Gender norms

Gender norms

A specific set of social norms that relate to relations between genders.

Positive deviant

Positive deviant

A person/group that goes against a social norm that we see as negative for our mission. These can be leveraged to achieve change.

Vignette

Vignette

Short stories about imaginary characters in specific contexts, with questions that invite participants to respond to the story in a structured way. You can use them to gather insights or to evaluate changes you are seeing following an activity.

Attitudes

Attitudes

What an individual thinks and feels about a behaviour or practice. While social norms are socially motivated (= linked to one’s perception of what others do or expect), attitudes are individually motivated, and focus on individual beliefs. Attitudes can be aligned to norms, but they can also be in opposition to them. The strength of the norm will determine to what extent a person will engage in a practice that is not aligned to their attitude. Attitudes can influence whether a person conforms to a norm or not; however, they are not in and of themselves norms.

Example: Attitude: “I think that girls should get married shortly after reaching puberty.” Linked norm: “I think that most girls in my community get married shortly after reaching puberty.”