Leveraging the socio-ecological model in social norms SBCC

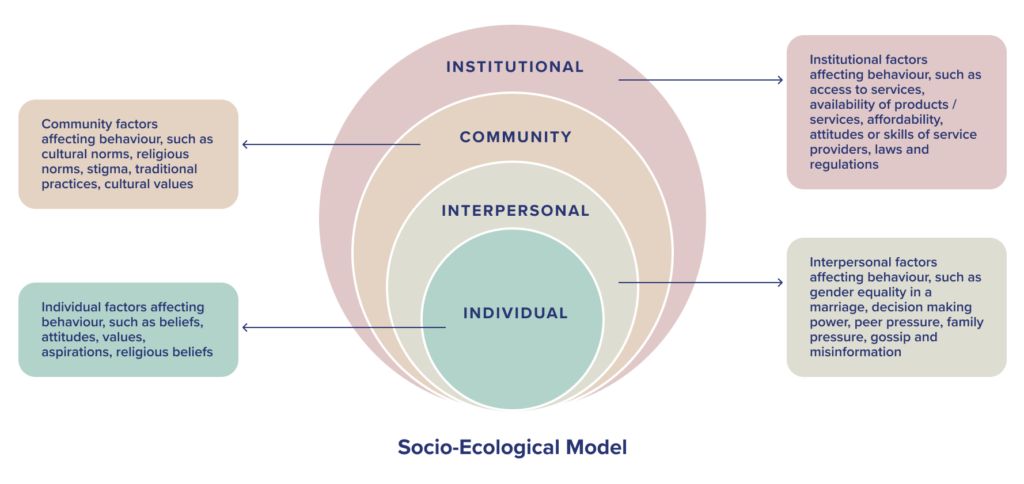

In the contexts we work in, communities tend to be tight-knit, and powerful social norms make up the fabric that keeps the community running. This means that successful social norms interventions need to address more than one level at the same time: individual, interpersonal, community and/or institutional levels.

A successful behaviour change intervention normally works to influence multiple levels, as shown by the diagram below. Keep this in mind: the final messaging strategy/ project/ activity you settle on, might be more successful if you address multiple barriers at once.

Interpersonal level

We pay attention to the actors we can and should involve, beyond our core target audience to key community-level influencers, but we ensure that the less obviously powerful are involved too. Through thorough reference group analysis, we have developed interventions that involve mothers-in-law, male peers and other community members whose influence is most prevalent at the interpersonal level. Our work in the Sahel on the La Famille Idéale intervention is a great example of this. La Famille Ideale is a suite of participatory tools for use by community mobilisers. The tools (a board game and facilitated couples’ conversation) target adolescent women directly as well as their husbands and other key influencers (such as mothers-in-law). LFI is being used by all four of MSI’s programmes in the Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Senegal) to create awareness and demand for the quality contraception services offered by MSI teams. Used by community mobilisers ahead of MSI outreach visits, the tool has proven successful in creating an enabling environment for conversations where young girls have no decision-making power. An initial evaluation found: (i) a 25% increase in adolescent reach in those sites using the tool; and (ii) the creation of community dialogue that was successful at dispelling myths about contraception.

The tools involve husbands in a discussion about FP, to show that husbands can and should be a part of these discussions; explore who can use FP, when and for what reason, challenging the norm that young couples should wait to use FP until they have multiple children; model the role mothers-in-law can play to support FP uptake, by exploring the role of this key reference group; and focus on the benefits of FP for birth spacing, shifting individual understandings and beliefs to give people the confidence to challenge the norm themselves.

Beyond the family, we aim to leverage existing opportunities in the community to create new champions where we can. Nigeria’s work on the Gagarabadau projet is a great example. Gagarabadau uses three complementary strategies, Tea Vendor business training, mobiliser-led peer to peer conversations and the diffusion of the term ‘Gagarabadau’ (a Hausa term used to describe a respected man) to engage men and address social norms linking large families to men’s status and the role of women in family decision-making and income generation. Results from a qualitative evaluation indicate that the intervention successfully engaged Tea Vendors and their wives to create community family planning champions. The community discussions that took place because of this engagement were able to start to overcome negative social norms related to family size and status, instead promoting that a responsible man is one who spaces births to have a healthy and successful family. This was reinforced by the peer-to-peer discussions and a wide and varied diffusion of the term ‘Gagarabadau’. Further, the emphasis placed during the training on shared decision-making saw Tea Vendor wives start to play a greater role in family business decisions and supported many to set up their own small business. This was a powerful way to role model these positive behaviours. Activities generated almost 4,000 referrals for FP services during a nine-month pilot, of which 47% were confirmed redeemed at nearby healthcare facilities.

Individual Level

MSI wants to empower individuals, championing positive deviants, and giving people the opportunity to assess for themselves if a social norm is worth challenging. By amplifying satisfied clients’ testimonials during mobilisation activities, we work to turn these women into our most effective community advocates, driving SRH norm change.

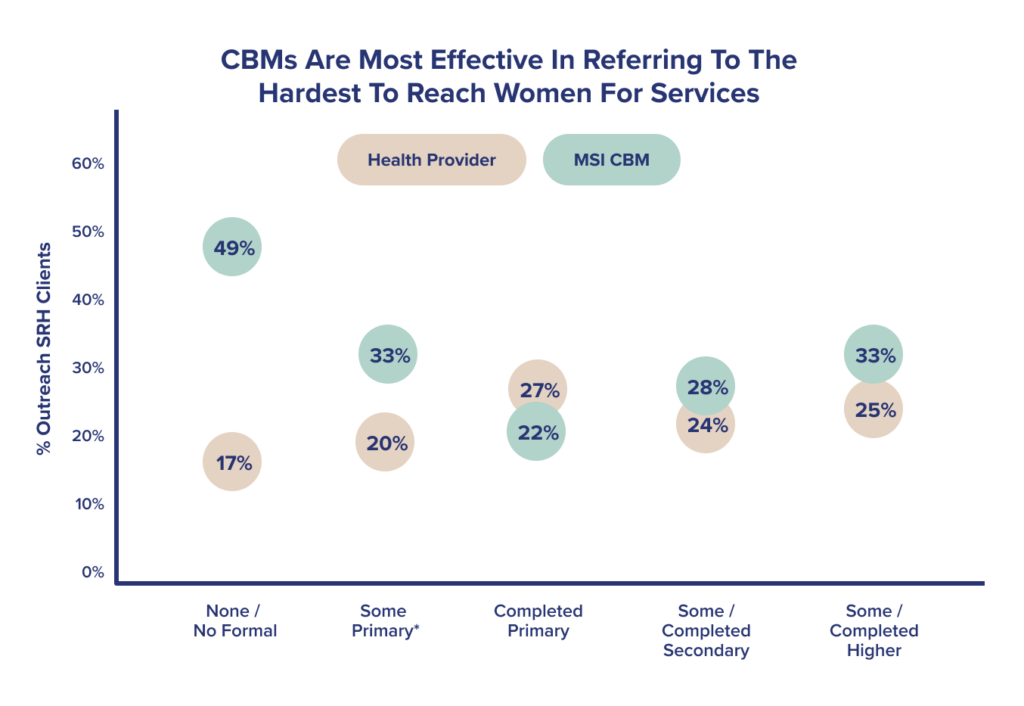

The numbers speak for themselves: 25% of adolescents and women without children taking up FP services in the Sahel cited personal recommendation as the most important source of information for them. This is especially important for more sceptical or underserved groups, such as nulliparous women (see chart), who may face extraordinary normative pressure to have children as soon as possible. Typically, MSI sees a limited number of ‘early adopters’ on the first 2-3 visits to a site. Subsequent visits see FP uptake increase significantly, stimulating community demand, and creating its own momentum.

In outreach service sites in rural Niger, where MSI expanded operations 3 years ago, the number of women and girls taking up FP services has doubled (from 15 to 30/team/day) in the last 18 months, and 80% of users now report community support and encouragement for modern contraceptive use.

Community level

MSI invests the time to understand each local context and work in collaboration with government and community partners to identify key leaders and influencers, crafting appropriate and culturally sound messages to create buy-in and support. This is a key driver of the longevity of any partnership. We engage community structures to gain acceptance, identify and create advocates who speak up in support of the activities. In certain conservative settings, this may only mean tacit acceptance from leaders – but any resistance from the community can prevent implementation.

This includes community partnerships, which can be great ways to find champions, opportunities, and ensure local adaptations. Leveraging their existing linkages with youth through routine activities or special events, MSI coordinates service provision with mobilization events that are taking place for adolescents. In Senegal for example, MSI works closely with the Centre Conseils des Ados to organize discussions about a range of topics including SRH, FGM, child marriage, SGBV and then provides services in discreet rooms within the Centre’s premises.

Community leaders are of course key actors in any social norm change work, being part of the reference group for many social norms we work on. Getting them on board can boost change and trickle down to the broader community. An example is our work in Zambia. Marie Stopes Zambia works with the health facility team to share local statistics on adolescent SRH like adolescent ANC attendance or deliveries (proxy measures to highlight the burden of teenage pregnancy) with community leaders during engagement meetings.

In addition, community leaders are engaged in a ”path game” activity here to understand the adolescent SRH journey and the challenges they face These are exercises that build empathy and understanding for adolescents among leaders, allowing them to walk in the shoes of young women and understand how the rights of adolescents align with the priorities of their community – but not necessarily with the current hindering social norms.

Institutional level

Where possible, we work with our Advocacy Team colleagues to publicise social norms change and work with institutions to embed social norms theory and practice. All of our country programmes work with community health workers (or their equivalent). We try to influence the CHWs’ experience at higher levels. We work with the national- and district levels to advocate for better, more-FP-integrated/focused training packages, and look for opportunities to increase government ownership of CHW payments. Most CPs will have worked on building CHW capacity through training. A stand-out example is Ghana, where the CP worked with the Ghana Health Service to develop a joint framework for SBCC and a roll-out/cascading plan for training.